After taking charge of the Disney Animation Studios in 2006, one of John Lasseter’s most immediate tasks was to see if Disney animators could exploit Disney’s other franchises, properties and trademarks. The result was not just a series of films introducing new Disney Princesses, or even an animated film focusing on one of Marvel’s more obscure superhero teams, but a film that focused on one of Disney’s most lucrative franchises, one based on a bear with very little brain, Winnie the Pooh.

Disney had not exactly been idle with the franchise since releasing The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, a collection of three cartoon shorts, back in 1977. The company had released three separate television shows based on the franchise (a fourth, My Friends Tigger & Pooh, would debut in 2007, run until 2010, and then return again in 2016), along with several video games. The success of these encouraged Disney’s Television Animation/Disney MovieToons division to release three full length theatrical films: The Tigger Movie in 2000, Piglet’s Big Movie in 2003, and Pooh’s Heffalump Movie in 2005, all filmed outside the main animation studios, largely overseas. If not blockbusters, the films had all enjoyed modest success and profits—more than many of the Disney Animated Features of that decade could claim.

In addition, Disney had released related products ranging from toys to clothing to kitchen implements to cellphone cases to fine art. Disneyland, the Magic Kingdom in Orlando, and Hong Kong Disneyland all featured rides loosely based on the 1977 The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh, and character meet and greets were available at all of the theme parks and the cruise ships. The franchise, Forbes estimated, was earning Disney billions annually.

And yet, the Disney Animation Studios had avoided doing anything more with Winnie the Pooh—perhaps not wanting to encroach on the classic shorts, among the last works that Walt Disney himself had personally supervised. Until John Lasseter ordered the animators to take another look.

The result is a blend of popular, child friendly—very young child friendly—elements with a nostalgic look back at the 1977 film, to the point of copying animation and even camera angles from the earlier film. Like that film, Winnie the Pooh opens with live footage of a child’s bedroom, with a door marked with a sign saying “C.R. KeepOTT” (with the R written backwards)—not, as some of you might be thinking, an invitation from Christopher Robin to go off topic in the comments below, but a genuine desire for privacy, immediately ignored by the camera and narrator John Cleese. Unlike that film, this is less a real bedroom than an imagined example of a child’s bedroom from, say, the 1920s—that is, the bedroom of a child who collects things. The camera pans around to show us antique books (including an old edition of The Wind in the Willows, another film Disney had brought to life in an animated short), and toys from the 1920s and earlier periods, along with “classic” versions of the Winnie the Pooh stuffed animals, and a copy of Winnie-the-Pooh—which, in another nod to the 1977 film, the camera lets us enter, as the opening credits start up.

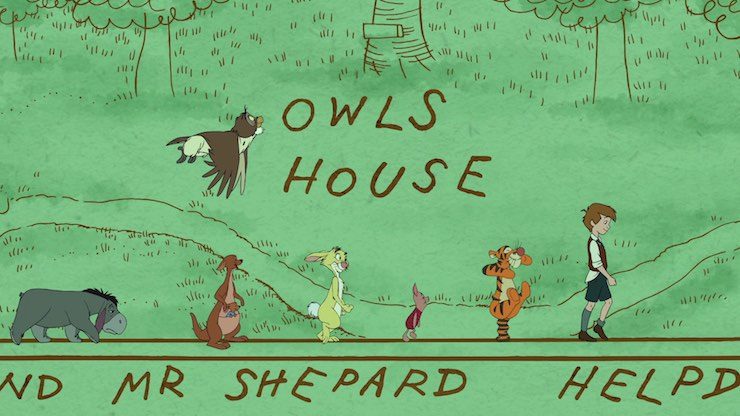

The opening credits aren’t quite identical to the ones in the earlier film, but close—with the camera panning around a map of the Hundred Acre Woods, introducing the characters that live there, including, of course, Pooh, all while playing an updated version of the “Winnie the Pooh” song, this time sung by Zooey Deschanel, in tones that hark back to the first cheerful recording.

As a further nod to nostalgia, the computer animated backgrounds drew heavily on the earlier film for inspiration, as did the animation cels, which, if inked by computer, were all drawn by hand—the official last time a Disney animated feature has included hand drawn animation cels. Animators worked to stay as close to the earlier character animation as possible. “As possible,” since the earlier film used much thicker inking, and showed the original pencil marks in many frames, something new computer processes were able to clean up for this film. It looks much neater and clearer as a result—giving a sense of what might happen if Disney ever decides to do some additional digital cleanup on their 1960s and 1970s film.

Disney couldn’t bring back the 1977 voice actors. But they could bring back Jim Cummings, perhaps best known for “voicing everything,” and who had voiced Winnie the Pooh for the MovieToons films, for Pooh and Tigger, and Travis Oates, who had taken over the role of Piglet after the 2005 death of John Fiedler, who had voiced the role in the 1977 The Many Adventures of Winnie the Pooh and in multiple other Winnie the Pooh productions. Otherwise, the voice actors were new to the franchise, including the well-known voices of Monty Python alum John Cleese as the Narrator, comedian Craig Ferguson as Owl, and veteran voice actor Tom Kenny (the voice of Spongebob Squarepants) as Rabbit , as well as the lesser known voices of Bud Luckey (primarily known for his cartoon and animation work) as Eeyore, and Kristen Anderson-Lopez (who wrote many of the songs in the film, and is perhaps best known for writing Frozen’s “Let It Go,”) as Kanga, with child actors hired for Christopher Robin and Roo.

For the most part, the voice acting is good to very good, with the exceptions of Owl and Rabbit—though in both cases, this is perhaps less because of the voicing, and more because of the disservice done to both characters by the script. Rabbit, in particular, is transformed from the serious, practical leader of book and former film into something perilously close to slapstick. Or I’m just reacting to hearing Rabbit sound like Spongebob Squarepants, which is slightly alarming. Owl, meanwhile, is a little more—what’s the word I’m looking for? Right. Deceptive than his previous incarnations, where he wasn’t aware that he was not as wise, or as educated, as he thinks he is. In this version, Owl does know—and yet pretends that he can read and knows exactly what a Backson is—terrifying the other characters in the process. It’s an unexpected take on the character, and one I can’t exactly embrace.

But if tweaked a few of the characters, Winnie the Pooh otherwise stuck closely to many aspects of the earlier film, including the conceit of remembering that the entire story happens in a book. In an early scene, for instance, the narrator, wanting to wake Pooh up, shakes the book around, sliding Pooh here and there, and eventually sliding Pooh right out of bed—a process that mostly serves to remind Pooh that he wants honey (nearly everything reminds Pooh that he wants honey) but also working as a hilarious interaction between text, story and animation. In a later scene, letters for the text fall on Pooh after he’s danced on them, and Pooh runs into a severe problem when, as the narrator says sadly, he gets so distracted by his rumbly tummy that he fails to notice that he’s walking right into the next paragraph. If not exactly as original as, well, the original film, it’s still a lovely surreal blend of story and text.

Another surreal sequence about the Backson deliberately recalls, in image and animation, the Heffalump sequence from the earlier film—which in turn was in part meant as a homage to the Pink Elephants sequence in Dumbo, in an illustration of just how significant that film was to the history of animation. This is by far the least imaginative of those three, but it’s one of the highlights of the film: a fun moment where the animated chalkboard characters leap into life.

And as in the earlier film, the plot is distinctly aimed at a very young audience, which is to say, this is the sort of film that plays a lot better when you are four and can laugh over and over and over at puns on the word not/knot—a thoroughly silly bit of dialogue that I could only appreciate because in many ways, I am still four.

That focus means that Pooh is almost entirely motivated by something completely understandable to the very young crowd: Food. Specifically, honey. Again and again, Pooh almost gets his longed for honey—only to lose it, or to discover it isn’t really there. It’s very sad, and completely relatable. More so, frankly, than the supposed main plot of the film, which starts when the characters find a terrifying note from Christopher Robin containing the word “Backson.” It does not take the characters too long to convince themselves that Christopher Robin is in terrible danger from the Backson and must be saved. It does take them a long while to do so. Kanga does some knitting along the way, and Tigger tries to turn Eeyore into a Tigger, and Piglet panics, and a balloon floats around, and Rabbit….Rabbit annoys me. It all leads to songs and bad puns and one admittedly awesome if minor twist, when the reaction to Owl flying is….not what you might be expecting.

But most of the film is about Pooh wanting honey, that is, right up until the moment when he has to choose between eating honey and helping a friend. THIS IS A VERY HARD MORAL CHOICE, everyone, even when you aren’t four, and it’s not hard to understand what poor Pooh is going through here even if you are technically a grown-up.

And as someone who is, technically, a grown-up, I thoroughly sympathized with Eeyore’s response to Tigger’s excited plan to turn Eeyore into a Tigger: Hide beneath the water, with a little straw letting him breathe. I’m with you, Eeyore. Stay an Eeyore. Don’t try to be a Tigger.

I suppose I could read more into both of these plots—the honey plot, with its focus on doing the right thing, and the Backson plot, with its focus on not letting yourself be terrified by imaginary things, both as moral lessons and as some sort of metaphor for the artistic process and/or life in 21st century America, but I’m not going to. Largely because I kept finding my attention occasionally drifting here and there, even though, at just 63 minutes, this is the second shortest film in the Disney canon, after Dumbo. Oh, the film has its amusing moments, and I loved the animation in the Backson scene, and I loved the conceit that the balloon almost—but not quite—had a personality of its own, and almost—but not quite—became its own character in the film. But in some ways, the stakes are almost too low, perhaps because it’s all too obvious—even to little viewers—that the Backson does not really exist. And while I’m all for teaching children that often, what you can imagine is much worse than the reality, in this case it does leave the characters spending rather a lot of time scared of nothing at all and doing very little thanks to that. It’s a bit hard to get emotionally invested, even if I do feel for poor hungry Pooh and Eeyore, who has to deal with the loss of his tail and Tigger trying to make him into a Tigger.

Initial audiences apparently had the same lack of engagement. Released on the same weekend as Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, presumably with the hope that parents with young children would want a less terrifying alternative, Winnie the Pooh bombed at the box office, bringing in just $50.1 million. The only bright side to this was that the short film was also one of the cheapest of the 21st century films—Frozen, released just two years later, cost about $150 million to make, in comparison to Winnie the Pooh’s $30 million budget, prior to marketing. With marketing included, Winnie the Pooh lost money on its initial release.

But this was only one minor glitch in what was otherwise one of Disney’s most successful franchises, and Disney was confident—correctly, as it turned out—that Winnie the Pooh would do well in the DVD/Blu-Ray market, eventually recouping its costs. Plus, Disney had something they thought looked a bit promising for 2012: a fun little thing about video games.

Wreck-It-Ralph, coming up next.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.